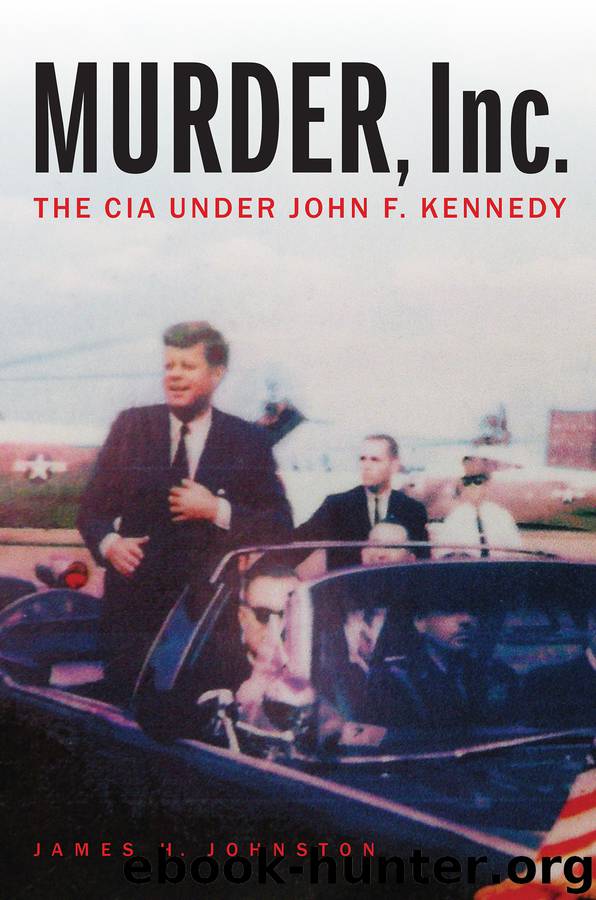

Murder, Inc. by James H. Johnston

Author:James H. Johnston

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: HIS036060 History / United States / 20th Century, POL010000 Political Science / History & Theory

Publisher: Potomac Books

21

An Investigation Hobbled from the Start

Within forty-five minutes of Oswald’s death, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover called Walter Jenkins, President Johnson’s aide, to summarize what the FBI knew. Hoover began laconically: “There is nothing further on the Oswald case except that he is dead.” He said the FBI had warned Dallas police that Oswald might be in danger, but to Hoover, that was water under the bridge. He had already decided the direction the investigation would take: It would be aimed at proving Oswald fired the fatal shots. Any public disclosure of the possibility of foreign involvement should be avoided. Hoover was focused on wrapping up the assassination as a simple case of murder and returning to business as usual. He concluded by telling Jenkins, ominously but somewhat inaccurately, that the FBI had intercepted a letter from Oswald to someone in the Soviet embassy who was in charge of assassinations. Hoover warned that “to have that drawn into a public hearing would muddy the waters internationally.” Hoover said he had already discussed his view with Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach.1

Such a bureaucratic attitude is understandable in Hoover’s case; a similar attitude at Robert Kennedy’s Justice Department is not. Katzenbach wrote President Johnson’s assistant Bill Moyers on November 26, the day after the funeral for John Kennedy, to urge the White House to make a public statement to stop the rumors about the assassination. The guiding principles should be the following: “The public must be satisfied that Oswald was the assassin; that he did not have confederates who are still at large; and that the evidence was such that he would have been convicted at trial. Speculation about Oswald’s motivation ought to be cut off, and we should have some basis for rebutting thought that this was a Communist conspiracy or (as the Iron Curtain press is saying) a right-wing conspiracy to blame it on the Communists.”2

In a book written years later, Katzenbach notes that he is criticized for this wording since it seems to imply a cover-up. He calls it a “badly written memo.”3 He did not mean, he argues, to limit the investigation of the assassination. Be that as it may, Katzenbach’s views in 1963 seem to square with the advice he was getting from Hoover, namely, wrap up the investigation quickly. Regardless of what he intended or what he thought in hindsight, his memo surely colored the White House’s views and underscored the political pitfalls of the slightest hint of a foreign conspiracy.

That Katzenbach’s memo reflected government policy at the time is reinforced by what U.S. ambassador-at-large Llewellyn Thompson, who had formerly been ambassador to the Soviet Union, apparently told the Soviet ambassador, Anatoly Dobrynin. In a top-secret cable of November 26, the Russian wrote the Presidium in Moscow:

The question also arises as to whether there is any connection now between the wait-and-see attitude of the U.S. authorities and the ideas conveyed by Thompson (though he himself may not be aware of this connection) on the desirability of

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15353)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14506)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12392)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12097)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12028)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5784)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5444)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5403)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5307)

Paper Towns by Green John(5191)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5008)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4963)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4502)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4490)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4447)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4390)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4348)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4325)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4198)